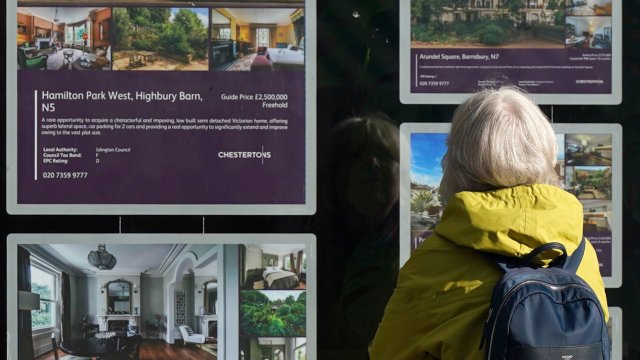

Fears are growing that Britain’s housing market will crash. With the Bank of England’s base rate expected to hit 6 per cent by the end of this year, there is good reason to feel concerned. Mortgage costs are soaring, hundreds of thousands of people are already struggling to pay them and fewer people are able to buy homes at all – data from HMRC shows that the number of homes sold in May this year was down 27 per cent on 2022.

In short: what’s certain is that there will be a fall in house prices, the question now is just by how much. New data from lender Halifax today shows that house prices are now falling at their fastest rate in 12 years as rising interest rates begin to feed through into the housing market. But predictions on how big the drop will be range from anywhere between 10 and 30 per cent in real terms.

When politicians and economists talk about the state of Britain’s economy, they often speak in medical metaphors. Our economy is very “sick” and rising interest rates are the “medicine”. The treatment might be “painful” but, as John Major once said, “if it’s not hurting, it’s not working.”

Continuing in this vein, let’s consider how close Britain’s feverish housing market is to a downturn. The cheap credit switched on as a form of life support after the global financial crisis in a drive to keep the housing market growing is gone. The medicine the Bank of England has decided will make the rest of the economy better is now higher interest rates.

Cheap credit sustained the housing market by keeping house prices rising even when wages were not keeping up in real terms. The Bank of England deliberately kept interest rates low to encourage spending during a time of economic downturn. This made mortgages inexpensive and fuelled rising house prices. Those prices hit a record peak in 2022, at the same time as housing affordability hit a record low.

The problem is that in allowing that to happen and, even encouraging it, the Government and the Bank of England have backed themselves into a corner.

Over the past two years, expert economists such as Roger Bootle and Josh Ryan-Collins repeatedly told me that cheap credit was masking a growing economic problem: the widening gulf between the real wages of workers and the price of homes.

Ryan-Collins is an associate professor in economics and finance at the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose. He has previously stressed in this column that this gulf made Britain “a pretty strong candidate for another massive bust in house prices”.

Bootle, chairman of Capital Economics and a self-described “long-term critic” of Britain’s housing market, was a leading voice in warning that there could be a house price crash in 2008. He cautioned last year that low rates had “fooled people into thinking everything is fine”.

Now, without them, it’s clear that things are not fine at all. A house price fall of between 15 and 20 per cent will be enough to plunge people who bought at the top of the market during the pandemic years into negative equity and rates of 6 per cent or more are widely regarded as an affordability tipping point for mortgage repayments.

Combined, this means that homeownership is going to look very different in years to come – a lot less like a good investment and a lot more like a risky bet. Owning a home for those people who have mortgages and are coming off fixed rates will be expensive. Houses will not be assets which go up in value automatically, leaving homeowners with piles of cash in old age, but, instead, costly purchases which people are still paying for in retirement.

“I think this could get quite a bit worse,” Ryan Collins told me this week. “I would bet on interest rates going up further and there being a serious downturn in house prices, which will have serious impacts for the economy as a whole – people will have much less to spend on buying things in the economy, and that will impact growth overall.”

“A crisis is coming in the housing market,” he added. “Unless there are interventions from the Government, which I am sure there will be, we will see repossessions and negative equity.”

The Government has ruled out intervening to help people pay their mortgages for now because doing so would run in direct contradiction to the Bank of England’s aims. It would pump money into the economy when the Bank is trying to stop people spending.

But if house prices do fall significantly and there is wider economic downturn in years to come – which the International Monetary Fund has warned could be a side effect of inflation and rising rates – the housing market might get help.

In the past, such as when we were in the post-2008 recession or emerging from the first Coronavirus lockdown, the Government has introduced policies to stimulate the housing market such as Help to Buy or stamp duty cuts because high house prices, as the Bank of England itself notes, make people feel confident and encourage them to spend money.

Whether they should do that ever again is questionable, though. What is being exposed right now is that Britain’s housing market as it evolved after 2008 – where prices grew along with the debts people took on to pay them – was precarious and vulnerable, relying on unsustainable monetary policy to keep it going.

Unless earnings increase dramatically, rising interest rates will mean house prices can’t go higher. This moment presents an opportunity to turn around and look at where we’ve come from since 2008.

The Government may yet intervene, but doing so by flooding the housing market with more debt would only prop up unaffordable house prices and prolong this pain.

Under Jeremy Corbyn, the Labour Party suggested house price inflation targets – similar to the overall inflation target – to make sure homes can’t become unaffordable because house prices soar above wages. Once radical, that policy is starting to sound more and more sensible. Truly affordable social housing, equally, is starting to look more and more attractive not only because building it generates economic growth, but because it means people have secure homes and money to spend on other things.

Chaotic cycles of boom and bust in the housing market have been normalised. Perhaps now is the time to question who that really works for.